LABYRINTHUS: CARLOS CRUZ-DIEZ

LABYRINTHUS

Enter free in color

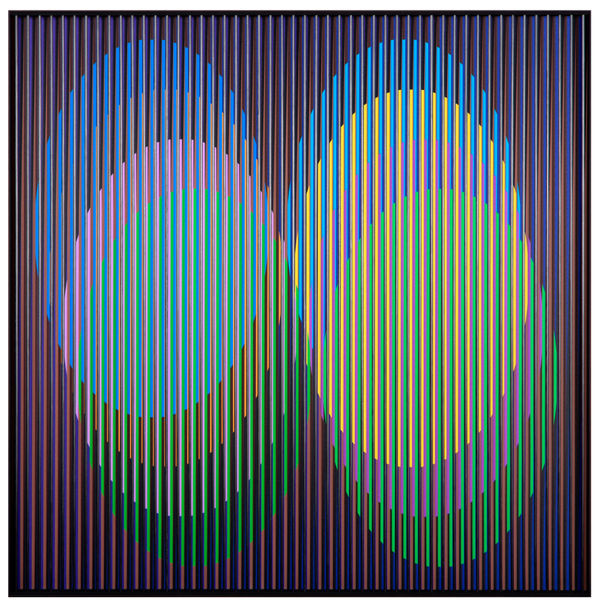

Carlos Cruz-Diez’s installation of an outstanding Labyrinthe de Transchromie – a project that he conceived at the end of the 60’s and completed for the first time in the nave of the Galerie La Patinoire Royale Bach in Brussels – is an important landmark in the artist’s long-time carreer.

Imagined in 1965 for the Galerie Denise René, it consisted of two rows of colored Plexiglas slats filtering and reflecting the light of the gallery’s showcase and thus disrupting the chromatic perception of reality. It was then extended in 1969 at the Museum am Ostwall in Dortmund, where the artist presented a more immersive version of the Labyrinthe de Transchromie, combining the colored slats’ effects to a right-angled layout. The Labyrinthe de Transchromie Bruxelles concretizes an idea that remained unachieved for more than half a century.

Contemporary materials (Bohemian glass in this case) and stable assembly and foundation techniques were introduced to give life to this monumental environment, the vital experience of color.

The visitor reaches the artwork by an inclined plane and is immediately immersed in the large installation, getting to experience in the flesh the extreme “sensorialization” of color. The experience involves the visitor’s whole body and is enriched as the external environment – particularly sumptuous in La Patinoire – interacts with the reflection and the illumination of the piece.

Litterally meaning “though the color”, this Transchromie invites the visitor to penetrate into color, on the basis of nine different shades ingeniously distributed by the artist in twenty five pairs of right-angled slats.

By juxtaposing these colored and transparent panels on a white, immaculate and reflexive surface over 200 square meters, the artist invites the visitor to stroll inside the color and to create by his progression and the addition of colors and entirely individual chromatic experience.

Bright colors, often primary, mixed by this Transchromie, open surprising perspectives and perform unexpected blendings. This work sounds like the living will of the artist on all the theories and practices he has conceived and defended throughout his long and prolific career.

First of all, as his fellow artists Jesus Rafael Soto and Julio Le Parc, founders of Kinetic and Optical art, Carlos Cruz-Diez conceives the work of art as a participatory work: the spectator modifies by his position and his movements the object his is looking at. This notion of movement is also a matter of time and introduces the fourth dimension in art.

Secondly, he considers that this work is the sum of the object and the subject inside a delimitated area, in all the variability of the individual experiences. This is why Carlos Cruz-Diez has promoted interventions in public settings since the beginning of his career, with an assumed aim of democratization of the art object. Art belongs to everyone and everyone experiences it.

Finally, his research on color is based on a scientific and empirical posture regarding the sensory and physical experience. The work of art is no longer autonomous and distant. It is no longer a unilateral proposal from the artist to the audience. The public and artists are indissolubly associated in his phenomenology, constituting somehow an assumed couple, by which the artist takes an amused and quasi-scientific distance on the effect produced on the spectator.

As with Soto and his Penetrables, or with Le Parc and his Continuels lumière, Carlos Cruz-Diez summons the subject at the very heart of his work, asking him to report on it through a whole personal, individualizing and “realizing” experience.

The Labyrinthe de Transchromie is an invitation to discover this individual experience, as a generous and enriching desire to share what the artist has imagined during his career. The artwork offers to everyone, wherever they come from, the opportunity to be confronted with them- selves, their perceptions, in a transparent way to the others.

This labyrinth is not really one indeed.

It opens long diagonal perspectives, straight lines towards the exterior space, sparing surprise effects and reassuring the visitor on the immediate possibility to find a way out.

Thus, this labyrinth does not enclose, it does not partition, it does not create anxiety. It is a place of convergence and encounter for a humanity in search for meaning and openness, communicating in color and sharing their sensations.

As you enter this labyrinth, the figures of the others are not absent. We perceive them particularly neatly, wherever they are. The others have also entered the experience and thanks to transparency, they get an opportunity to share and exchange their feelings.

As we discover this realization of spirit and senses, two references come to our mind, stemming respectively from Greek mythology and the Western history of art.

King Minos asks his architect, Daedalus, to design a labyrinth to hide the monster born of the adultery of his wife Pasiphae with a bull. Every nine years, Aegeas, King of Athens, is forced to deliver seven boys and seven girls to the Minotaur, who feeds on this human flesh. Theseus, son of Aegeas, volunteers to go into the labyrinth and kill the monster. Ariadne, who wishes to marry Theseus, gives him a ball of thread so that he can find the exit.

Here, there is no need to kill or be a prisoner. We enter this labyrinth as free beings, in the absence of any monster. This archetypal meeting of the Labyrinth plunges us into color and the peaceful light of spirit and science, unlike the labyrinth of Theseus that symbolizes taboo, violence, fear and death. Our Ariadne thread is the aesthetic and sensible experience that, at any time, takes us out of ourselves with the cathartic feeling of an initiation. Another parallel, in art history this time. In Neoplatonic metaphysics from the Middle Ages, at the beginning of the 12th century, the abbot Suger, then in charge of the abbey of Saint-Denis near Paris, expresses a strong and vibrant conception of beauty as a luminous form, emanating from the divine source and allowing, through the contemplation of objects transfigured by light, to go back to its origin, less sensitive and more intellectual.

Light, the ultimate divine essence that reveals the right, the good and the beautiful,must then enter the religious buildings of the Western Middle Ages: this is how the rupture takes place with the obscure and stocky Romanesque style, and how was born in Saint-Denis the architectural Gothic style, bright and slender. In all Europe, wonderful stained glass, window and rosettes started to bloom.

How could we not see in the work of Carlos Cruz-Diez and in this Transchromie a direct connection with the great tradition of Western stained glass, a will to use light and color to escape from the obscure cave of a materialist era craving for openness and tolerance, a will to reach justice and beauty?

To enter into color, as a free being, as if color were an airlock, and to come out mentally and spiritually transformed... Isn’t it, for an artist, one of the most generous and monumental proposal made for a public that Carlos Cruz-Diez has never ceased to enchant and surprise?